Obligatory Race Report!

The Tevis Cup, 2018

Now that I’ve been back home for a few days, work is back under control, and I have had a few nights of good sleep behind me…time for a recap! Tevis needs no introduction really – it’s in a league all its own, was the first endurance ride I’d ever heard of, and was the ride that got me interested in riding a horse for long distances over challenging terrain. It is the granddaddy of endurance - the Boston Marathon, the Kentucky Derby, Wimbledon, and the Tour de France of our sport. To say it’s iconic is an understatement of significant magnitude.

So back in 2014, when I first started training for the sport with my trusty mustang Lilly, it was with Tevis in mind. And then I did my first 30-mile race, thought I was going to die, and wondered what insanity had possessed me to even consider riding longer than that? The insanity passed quickly (or perhaps intensified), because soon I was riding 50-mile distance, then 75 miles, and was training for a 100. Lilly and I got our first 100-mile completion earlier this year, and with that last hurdle covered, set our eyes on the last Saturday in July – Tevis! I even convinced fellow Zonie MJ to come with me (it didn’t take much convincing), and we spent the next several weeks getting our crews organized, a logistics plan laid out, and conversed with as many Tevis riders as we could to get some insight into the trail and strategy on how to ride it. One does not simply show up and ‘ride’ Tevis!

Tuesday, Travel Day 1 – first leg was to Barstow, to a simple but very pleasant Horse Motel about half-way between here and Auburn. Of course, we left on the hottest day of the year, 117 degrees in the shade. Ugh. To mitigate some of the nastiness, we left around 5 PM so that at least there would be some respite when the sun went down. Barstow was still over 100 degrees even in the middle of the night but 1) it was a dry heat (that’s a joke) and 2) the Horse Motel had electrical hookups, so I got to run the LQ’s AC all night without pulling out the generator. Of course, ‘all night’ meant 4 hours, as we only wanted to rest for a few hours before hitting the road early to beat the heat again as we traveled the rest of the way.

Wednesday, Travel Day 2 – we made it to the Auburn Fairgrounds, the ‘finish line’ of the race, only to find out that our designated horse camping area had inadvertently been leased out to another group, so whoops! – no where to park the horses. Fortunately, there were still 2 open stalls in one of the barns, so we dropped a check to reserve them for the weekend. Whew! Tevis Gremlins #1 averted! We had a lovely “Official Tevis” BBQ dinner on the fairgrounds that night, and I got to catch up with my 20 Mule Team 100 partner Lucy (who is about as knowledgeable as they come about Tevis, and was an IMMENSE source of information and encouragement). If you had a chance to check out the Tevis live cast throughout the weekend and heard a lovely voice with an English accent – that’s my girl Lucy. She’s in a league by herself for sure!

Thursday, Pre-Ride and Robie Park – we took a quick pre-ride to cover the last few miles of trail in the morning, before heading up to the starting line camp, Robie Equestrian Park, 100+ miles away. It was on this portion of the journey that Tevis Gremlins #2 struck, in the form of a massive trailer tire blowout that took half my fender with it

:( MJ and her husband circled back to transfer Lilly to their trailer while I waited for US Rider to get a driver out to assist, and angel-in-disguise Stacy (one of MJ’s crew) stayed with me to keep me company. 3+ hours later the fender was cut away, the spare slapped on, and we were back in business! On to Robie! It was there that I met up with Crew #1, Christina, who would be staying with me for the start and then doing all of the rig-moving on Saturday.

:( MJ and her husband circled back to transfer Lilly to their trailer while I waited for US Rider to get a driver out to assist, and angel-in-disguise Stacy (one of MJ’s crew) stayed with me to keep me company. 3+ hours later the fender was cut away, the spare slapped on, and we were back in business! On to Robie! It was there that I met up with Crew #1, Christina, who would be staying with me for the start and then doing all of the rig-moving on Saturday. Friday, Ride Meetings, Horse Vetting, Crew Prepping, and Bear Sightings – Friday was a whirlwind of activity – there wasn’t enough time in the day it seemed for what we wanted to do! Crew #2 (Rianne and Pam, collectively known as RIPA) showed up, and we spent some time getting their SUV loaded up with all the gear they were going to need for the first one-hour hold vet check (Robinson Flat, 36 miles in). Tevis is an exercise in logistics, being a point-to-point ride. In my case, RIPA was spending the night in Auburn and going directly to Robinson’s, which meant that everything I needed (or MIGHT need), needed to go with them before they left Robie, so it would be waiting for me at the first check. Everything else would stay with the trailer and go with Christina, who would drop the trailer at the second one-hour hold vet check (Forest Hill) before meeting me at an intermediary check during the canyon section of the ride. But more on that later – suffice to say that it was quite stressful going through the multiple checklists to ensure that I got all my gear split correctly between my crew!

Friday, Ride Meetings, Horse Vetting, Crew Prepping, and Bear Sightings – Friday was a whirlwind of activity – there wasn’t enough time in the day it seemed for what we wanted to do! Crew #2 (Rianne and Pam, collectively known as RIPA) showed up, and we spent some time getting their SUV loaded up with all the gear they were going to need for the first one-hour hold vet check (Robinson Flat, 36 miles in). Tevis is an exercise in logistics, being a point-to-point ride. In my case, RIPA was spending the night in Auburn and going directly to Robinson’s, which meant that everything I needed (or MIGHT need), needed to go with them before they left Robie, so it would be waiting for me at the first check. Everything else would stay with the trailer and go with Christina, who would drop the trailer at the second one-hour hold vet check (Forest Hill) before meeting me at an intermediary check during the canyon section of the ride. But more on that later – suffice to say that it was quite stressful going through the multiple checklists to ensure that I got all my gear split correctly between my crew!In-between gear prep, I also attended a First-Time Rider Meeting, where an experienced Tevis Rider gave us additional tips about how to ride the trail (and where we had our first sighting of the Camp Bear, who waddled in from the meadow like he owned the place - which I imagine he did), and meandered his way through the trees and into the camp area. Robie Park is huge though, so he quickly disappeared out of sight…for a bit anyway. I got checked in, Lilly got vetted in, my crew attended the official Crew Meeting, we all went to the main Rider Meeting (which was when the Camp Bear stole a grain baggie before being chased away by RIPA, who left the meeting early to get on the road back to Auburn), ate a nice dinner, and tried to get some sleep for the Big Day!

Saturday, Tevis!

3 AM came quite quickly, though I didn’t get much sleep the night before. I went to bed reasonably early, but the Camp Bear decided to visit some of our neighbors at about 130 in the morning, and I was unable to go back to sleep after that. Christina got Lilly prepared, I got myself prepped, and at 430 I swung my leg over and walked out of camp to the start. The official starting line is a couple of miles away, but that works in our favor as the horses get a nice walking warm up before the insanity begins. I was a little worried about the start, mostly because my sometimes-grumpy mare takes great offense to having strange horses crowd her (she sometimes takes great offense to even her closest equine friends crowding her), but she was the perfect angel even when there was some bustling and jostling around while we waited for the magical 515 start time.

And we were off!

With about 150 horses all starting at the same time, it’s a little challenging to ‘ride your own ride’ for the first few miles – the herd takes off, you settle into wherever you start, and that’s the pace you ride at until the trail opens up a few miles in at the base of the long climb up Squaw Valley to Emigrant Pass. It was a brisk ride to the base of the climb, but then we settled down and took it slow up to the top – every Tevis mentor I had spoken to had reiterated the same thing – do NOT blast up the long Squaw climb, even though the footing is great and your horse feels fresh. A lot of horses who catapult up the mountain end up on fluids at Robinson’s or pulled later for being too tired. We took our time, walking the inclines and only trotting when we got to the flatter areas. As a result, the horses felt great at the top, and we continued through the Granite Chief wilderness area.

I think this was my favorite part of the ride. Despite the smoky air, the views were breathtaking, the terrain technical and challenging, but we made decent time as we travelled, navigating the imbedded boulders obscured by the ubiquitous dust, sloshing through boggy wet areas (not too much in the way of bogs, given how dry it’s been this year), and rock-hopping over rocky sections.

About 20 miles in when got to the famous Cougar Rock, and my intention had always been to go up and over (assuming there wasn’t a line of horses in front of us). There wasn’t, so I pointed Lilly to the Rock and away we went. The secret to getting over this giant somewhat vertical outcropping is to keep the horse moving forward (not a problem with go-go-go Lilly), head straight up to start (again, not a problem), then turn to the RIGHT and follow the last section up and over. Lilly missed the memo on going RIGHT, and pilot-error on my part, I didn’t have a tight enough hold on the right rein to keep her pointed in the correct direction. So, mustang started to go LEFT, which is a one-way ticket to no-where-good/good thing I have air-vac insurance, so I hauled her to a stop and tried to get her turned around. She did, but only so far as to face DOWN the direction from where we just came from. HEAVY SIGH. Cougar Rock is scarier looking down than up! I decided that trying to go up the Rock was not meant to be this year, so carefully navigated back down (which mostly meant holding on for dear life and hoping the pony didn’t stumble) and took the bypass. Next time I’ll have my sh*t together and we’ll make it up and over!

Our first vet check was a few miles later, at Red Star Ridge. It is just a ‘gate and go’, which means as soon as the horse passes the vet check we can hit the trail again. We were able to get vetted in pretty quick, Lilly scarfed down some water/alfalfa in a bucket (her favorite treat out on the trail, and great combination as it gets both fluids and food into their belly at the same time). Just a few short miles later and we pulled into Robinson Flat about 1130, our second vet check and the first mandatory 1-hour hold period, at the 36-mile mark.

My wonderful, amazing crew of RIPA met me on the road and got to work untacking Lilly and sponging her off to get her cool and to pulse criteria. It was already warming up – the cool morning air had been left hours behind us. Lilly pulsed down quickly, and we vetted in at the same time as both Ashley Wingert and MJ, who we had been riding with off and on throughout the morning. Once vetted we went back to the lovely crewing area set up for us, and while I relaxed and ate some real food, Rianne and Pam took care of Lilly and me respectively. I changed into my ‘cooling gear’ clothes for the next section – the hot, humid, and dreaded canyons – and our hour was up just like that.

Unfortunately, I was destined to ride the rest of the trail alone. Despite vetting in at the same time, I think my scribe did the math wrong, as my ‘out time’ was 5 minutes behind MJ and Ashley. Drat! MJ headed out first, and it turns out that Ashley ended up pulling at Robinson’s due to her horse not doing as well as he should. I wasn’t worried about riding alone, as there are always people out there on the trail with you in different sections, and Lilly is fine with forging her own trail. So off we went!

Out of Robinson’s and it’s a bit of an overall downhill trek to the next water stop (Dusty Corners, which lives up to its name because the dust was everywhere), then past Pucker Point at mile 48. I shared a video of Pucker Point on a previous post, and honestly it’s not that bad. I wouldn’t have even known that this was the infamous landmark had the riding buddy I picked up after Robinson’s not pointed it out

:) Then it was on to Last Chance, another vet check and gate-and-go, and the literal last chance to reconsider your decision of setting foot into the canyons. I didn’t reconsider, and off we went!

:) Then it was on to Last Chance, another vet check and gate-and-go, and the literal last chance to reconsider your decision of setting foot into the canyons. I didn’t reconsider, and off we went!

Canyon #1 – the longest, steepest, and most perilous of the bunch. A lot of riders hop off and walk/jog down to the bottom to be efficient and save their horses for the climb out, but my body doesn’t allow me to be that lucky. Lilly has to cart my arthritic ass everywhere, but she’s such a good downhill horse that we didn’t lose any time going down the steep switchbacks. I just needed to hold on and stay balanced, and she wound her way down the narrow trails until they spit us out at the Swinging Bridge. Once across (and yes it does swing a bit), we encountered the one and only snarky rider on the whole journey. Before crossing the Swinging Bridge riders can take a short trail down to the river to cool off in the water directly. When I crossed, there were probably 15 horses down there and I could already hear people yelling about something – too much drama for me, and I had already planned on stopping just past the Bridge where a natural water source bubbled out of the rocks by the trail about 1/8 mile up. A few other riders also had that idea, so there was a short line of horses on the single-track waiting their chance to get a drink prior to making the brutal climb out. The rider who crossed the bridge after me had come from the river, where apparently one of her horses (being ridden by a catch rider) was stung by some bees, and in a panic to get away scraped up his leg on the rocks. She was bound and determined to get out of the canyon as soon as possible to tend to her horse, and was understandably upset. She was yelling at everyone to keep moving and not stop so she could get out, nearly ran into Lilly in her desire to get past (and got a fairly serious double-barrel kick backwards from that bad decision – Lilly wore red ribbons on both ends to warn others to not crowd her – fortunately I don’t think Lilly connected, but the rider began yelling all over again). When it was Lilly’s turn to drink, I let her do so, for as long as she wanted. The rider began yelling again, ordering me to keep moving so she could get out of the canyon. Ummm…no. I politely, but firmly told her that I was going to let my horse drink, and when there was room on the trail I would be happy to let her pass…but my horse was going to get hydrated first. She didn’t press me after that, and about 30 seconds later we were on our way. I was able to pull over on one of the switchbacks not much farther up, and the two horses and riders were out of my hair finally. I did hear additional yelling for most of the climb, as the trail didn’t allow much passing and there was a LONG line of horses trudging up at the same time. I hope the horse ended up being okay – from what I could see the wounds seemed mostly superficial, and I know it was a scary thing to be at the bottom of the toughest canyon with an injured horse.

First and last drama behind us, we made our way out of that b*tch of a canyon. We weren’t fast, but fairly steady. Lilly is a better downhill horse, but is a decent climber if not overly fast. It did seem to go on forever, and just when I thought the end was in sight, there were more switchbacks. But finally it ended, whew! We spent a few minutes at the top in Devil’s Thumb, which was a water check/aid station, in order to slosh Lilly with water to cool her out. The volunteers were super helpful all day, and Lilly met a couple of her ‘Facebook fans’ who were volunteering and recognized our neon green colors!

After Devil’s Thumb it was just a mile to Deadwood, another official vet check and gate-and-go before descending into the next canyon. Lilly passed with flying colors, I dunked myself in more ice water and had my water refilled, and off we went. The second canyon wasn’t as bad as the first, but it was still rocky, steep, and long. And hot. I heard that the temps in the canyons reached 115, and I could really feel the humidity in the air. But onwards and upwards we trudged. It spit us out at Michigan Bluff, another water stop/aid station, and a busy and bustling whirlwind of activity. I spent a few minutes getting Lilly cool, and once again the volunteers were so helpful in holding her while I used the porta-potty and got my waters refilled. I did do a good job of staying hydrated all day, as I peed at almost every check

After Devil’s Thumb it was just a mile to Deadwood, another official vet check and gate-and-go before descending into the next canyon. Lilly passed with flying colors, I dunked myself in more ice water and had my water refilled, and off we went. The second canyon wasn’t as bad as the first, but it was still rocky, steep, and long. And hot. I heard that the temps in the canyons reached 115, and I could really feel the humidity in the air. But onwards and upwards we trudged. It spit us out at Michigan Bluff, another water stop/aid station, and a busy and bustling whirlwind of activity. I spent a few minutes getting Lilly cool, and once again the volunteers were so helpful in holding her while I used the porta-potty and got my waters refilled. I did do a good job of staying hydrated all day, as I peed at almost every check  :)

:)I was definitely feeling the heat at this point though, and the first signs of ‘uh-oh’ were on the horizon. I dunked myself in ice water again, and made my way 1.5 miles away to the next vet check, Chicken Hawk (i.e., Pieper Junction). My wonderful crew Christina was waiting for me there (along with MJ’s crew Stacy, as they had driven together). We got Lilly vetted in – she still looked really good – while I sat on a park bench and rested for a few minutes while Lilly ate. I was definitely starting to feel it then – I wasn’t (yet) nauseous, but I’ve been heat-sick enough times to know when my core body temp has been exposed to too much for too long. But, I had one more canyon to go, the sun was starting to go down and it was a *little* cooler, and I hoped that the upcoming one-hour hold at Forest Hill 4 miles away would be enough to perk me up and see me through to the end.

So off we went! We were totally alone at this point, with riders still coming in behind me but no one really in front of me. Lilly was not impressed at being pulled away from her delicious snack to once again forge on into another canyon, and though she walked out at a decent clip, she really didn’t want to do more than that. And I really didn’t have the energy to kick-kick-kick her into maintaining a trot, though we did manage some trotting going down into the 3rd canyon, whose descent was not that steep. It was fairly steep coming out though, so we walked the rest of the way into Forest Hill.

I have never been as happy to see my crew as I was at that point! I was beat, dizzy, and probably partially delirious. Lilly looked great, no surprise there! Rianne got her vetted in and she passed with flying colors – we didn’t even cool her off, as we were pushing the extended cut-off time as it was, and just walked up to the vet area and pulsed her through. Good pony!

I was carted (literally) back to my LQ – another luxury of Forest Hill, our trailers can make the journey – with Pam clearing a path with the “I got this, I’m a doctor” – don’t leave home without at least 2 doctors as part of your crew! I stumbled into bed with water and some electrolytes, and my medical staff conferred with me regarding what was going to happen next. They were willing to duct tape me to the saddle and send me out into the night, but in the end I decided to take the Rider Option. Had I not been pushing cut-off times and had the opportunity to walk the majority of the way to the finish, I may have been able to do it. But as it was, I was going to have to hustle every step of the way to not get pulled for overtime, was still dizzy and a little nauseous at this point, and I had some tough trails ahead of me. If I was going to get pulled, it was better to do it where I could easily be hauled out, as opposed to one of the more remote checks where I would potentially be waiting until morning (without any LQ creature comforts). Creature comforts won the day, and I was done.

Christina had joined us by then, so my three crew got everything packed up, Lilly loaded, and me piled into the back seat of the truck so I could lay down for the trip back to Auburn. I don’t remember much, other than Christina doing a stellar job at navigating the windy and narrow roads in the middle of the night without missing a beat. She got Lilly tucked into her stall, me tucked back into bed, and then kept semi-watch on both of us until morning. As anticipated, I did end up driving the porcelain bus in the middle of the night, but felt so much better after – I joked that in the future just make me puke immediately!

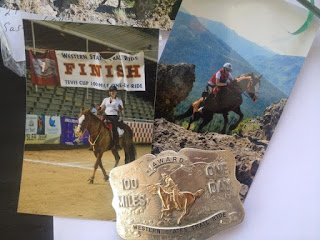

Even though I didn’t make it to the finish, Lilly looked fantastic and I have no doubt that she would have been strong enough to complete had I not been the weak link. And I was proud of two of my friends who also completed this year – MJ and Tammy. And, as a super bonus – 2 mustangs finished in the Top Ten, and one of them, MM Cody, won the prestigious Haggin Cup, awarded to the horse in the best condition at the end of the ride. It’s the first time that a mustang has won this title, and I was thrilled to be there to see it!

We hit the road Monday and overnighted at the Horse Motel in Barstow, then Tuesday I made my way to Prescott Valley so Lilly could do her post-ride resting at Julia’s, and hang out with Wyatt. She showed up at Julia’s ranch in raging heat, and has been tormenting the geldings since.

Next up, I’ll be taking both mustangs to Virgin Outlaw XP at the end of September. I had been thinking of going to the Virginia City 100, but that’s another 2 day haul each way and after the Tevis journey, I’d like to stick with something a little easier and closer to home for the next outing.

Next year I’m planning to be back at Tevis – a plan has been percolating about how to successfully complete this bad boy – I won’t say more than that as the plan is still in its infancy and things could change, but I know that Tevis hasn’t seen the last of me and Lilly quite yet!

And I have to give a final shout-out to my crew: Christina, Pam, and Rianne. They were absolutely fantastic all weekend, and made everything so much easier from start to (almost) finish. We had a wild and crazy adventure together, and I couldn’t have asked for nicer gals to share it with! And to honorary crew Stacy, who stayed with me for the whole tire blowout fiasco, went to the local tire store the next day to pick up my spare, helped me at Chicken Hawk, and was ready to pitch in and assist with whatever I needed all weekend. You’re a star!

2018 Ride Stats

Wyatt “On Vacation” Earp, 9/10 165 LD Miles, 150 Endurance Miles

Liliana “The Horse is Fine but they Pulled the Rider” Vess, 7/8 135 LD Miles, 150 Endurance Miles

Happy Trails!

Andrea, Wyatt, and Lilly